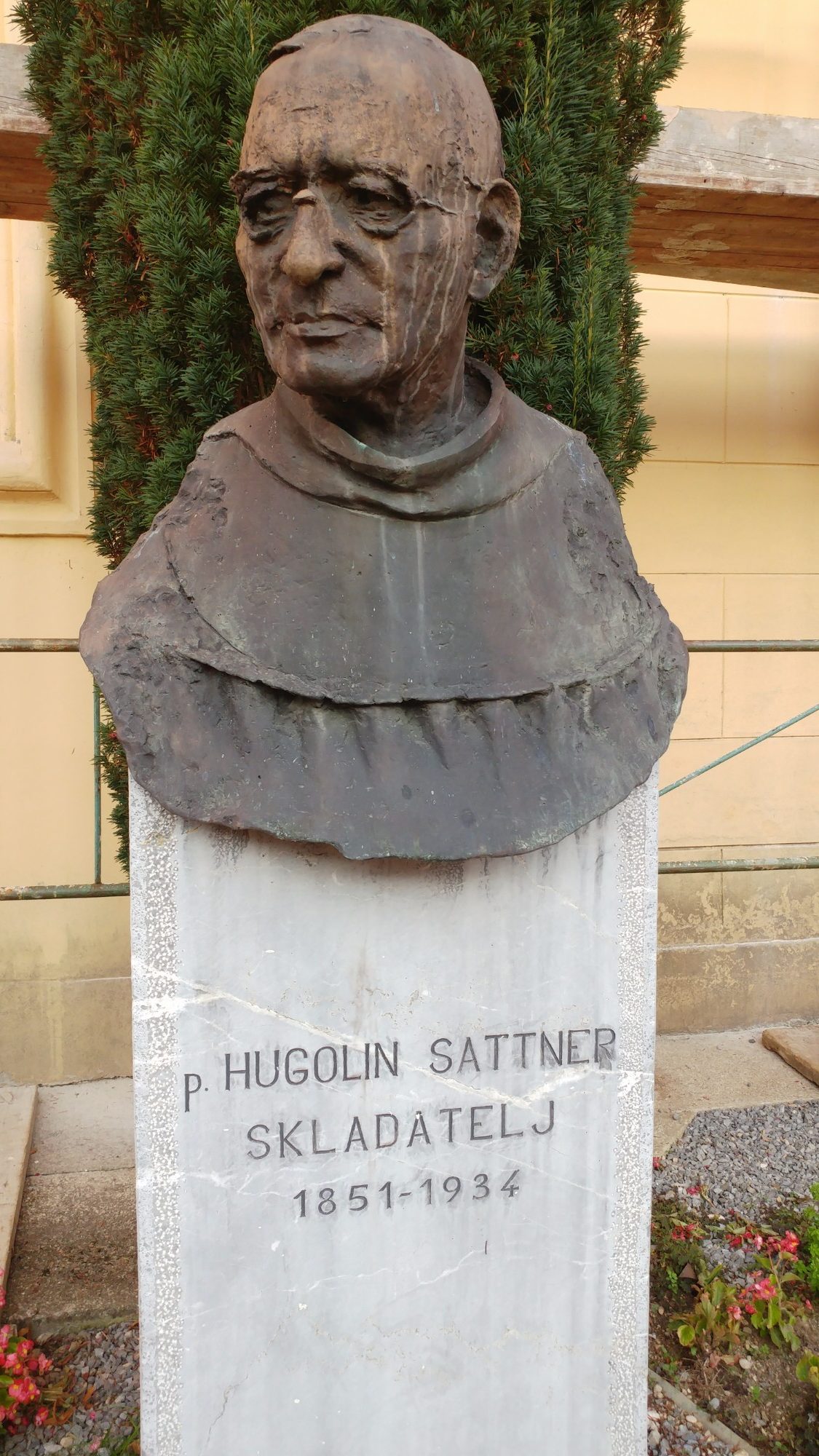

A bust of Hugolin Sattner by sculptor Mirsad Begić stands to the left of the Franciscan Church. The Franciscans had the monument erected in honour of their former friar and composer in front of the monastery in 2002.

Hugolin Sattner

Church musician, Franciscan friar and composer Hugolin Sattner (1851–1934) devoted most of his creative imagination to liturgical vocal compositions. Stylistically approaching the musical reforms of the Caecilian movement, the composer tended to discontinue the application of folk elements. Also a publicist, Sattner wrote discourses on music, reviews of works or performances and reported on the current choral music scene. His exhaustive writings discussing Slovenian organ music are also of great value.

Sattner obtained his first musical education while attending grammar school, by taking lessons in music theory, violin, piano and organ. Later, he became a monk in his native Novo mesto, where he was also an organist at the Franciscan Church and taught music. In 1876, the year in which he embraced the ideas of the Slovenian Caecilian movement and began to fervently espouse church reform, was a landmark in his musical career. An active follower, he was the movement’s board member, secretary and vice-president, as well as long-standing president of the Caecilian Society at the Ljubljana Archdiocese.

Aiming for serious reform of church music, Sattner attended a course in Gregorian chant in Graz, where he also learned about Renaissance vocal polyphony, especially by attending performances of compositions by Palestrina and Orlando di Lasso. Returning to Ljubljana in 1877, he applied this newly acquired knowledge and insight to extensively revising church music under the auspices of the Caecilian Society at the Ljubljana Archdiocese, which founded an organ school and launched a monthly journal, Cerkveni glasbenik (Church Musician). In 1878, Sattner published the discourse Cerkvena glasba, kakošna je in kakošna bi morala biti (Church Music as It Is and as It Should Be).

In Ljubljana, Sattner held various positions within the Franciscan monastery, and also served as the regens chori of the parochial choir. It was as late as at the age of fifty that he applied himself to composing. He studied composition under the tutelage of Matej Hubad, and succeeded in refining his musical texture grounded on Caecilian principles. He scored most of his work at the beginning and during World War I.

The foremost examples of his sacred music include Missa Seraphica, a piece notably performed in 1931 in Nôtre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, Te Deum, Jeftejeva prisega (The Oath of Jephthah) and the cantatas Oljki (To Olive Tree) and Soči (To Soča River). It was the oratorio Assumptio Beatae Mariae Virginis (The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary) that garnered particular acclaim in Slovenia. Dubbed “the oratorio for the Slovenian people”, the work is one of the rare specimens of the genre, besides some eighteenth-century compositions by members of the Accademia Philharmonicorum Ljubljana. In his characteristic style, Sattner’s musical texture foregrounds the solo voice and assigns accompanying roles to the organ and choral parts. Even composer and merciless critic Marij Kogoj was unstinting in his praise of the oratorio.

Some of Sattner’s secular compositions worth mentioning are the musical settings of poems by Simon Gregorčič, the lieder Zaostali ptič (Delayed Bird) and Naša zvezda (Our Star) as well as cantatas. His most extensive secular work is Tajda, an opera written in Sattner’s signature style dominated by the rigorous dictates of the Caecilian movement and integrating elements of Romantic music.

Maia Juvanc