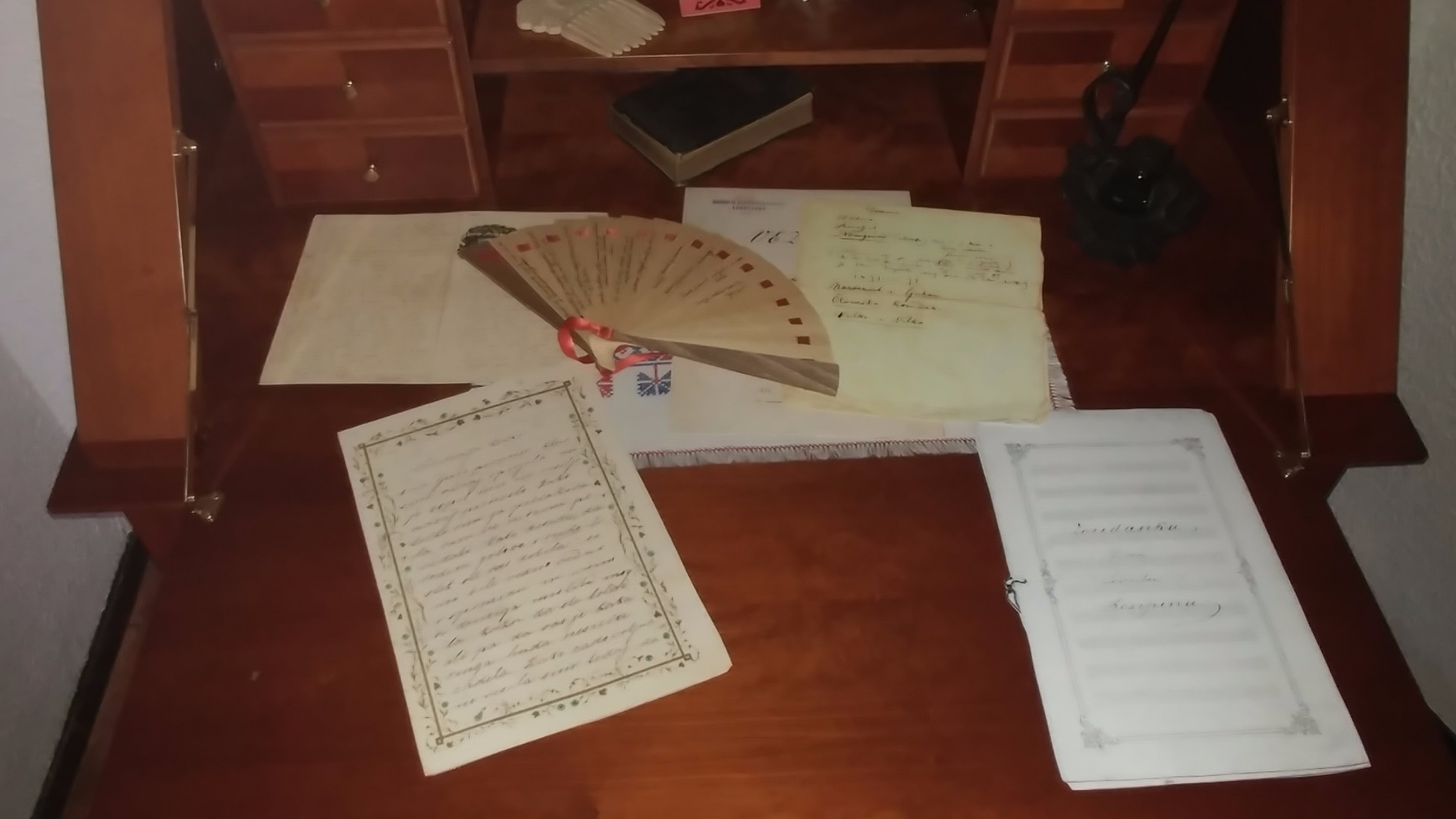

The Josipina Turnograjska memorial room at Turn Castle is located in the chamber designated for Saturday mass by the residents of the retirement home, which has been established in the Castle for decades. The room contains two display cases and a replica of Josipina’s writing desk. Almost no artefacts have survived, having been either confiscated and/or destroyed during the war.

The display cases contain photographs, and facsimiles of some of her works, none of which is a musical score. Josipina’s entire sheet music legacy is kept in the National and University Library’s manuscript collection (the complete list of her works is compiled in Moč vesti (The Force of Conscience by Mira Delavec). Other exhibits, including wooden bookmarks and fans, are reconstructions of objects originally used by Josipina. Some copies of love letters that Josipina addressed to poet and politician Lovro Toman, whom she promised to marry in 1850, are displayed on the desk. The couple’s written correspondence offers an interesting insight into nineteenth-century society circumstances and relationships.

The walls of the memorial room are adorned with copies of photographs. An interesting artefact is the zither, which Josipina supposedly played, although her correspondence (the only entirely preserved collection in her legacy) makes no direct reference to this type of instrument. Despite the fact that the manuscript of the singspiel Črtomir in Bogomila (Črtomir and Bogomila) has not survived, some references in her letters suggest that she worked on this piece.

Josipina Urbančič Turnograjska

The first Slovenian female poet, author and composer, Josipina Urbančič Turnograjska (1833–1854) wrote in Slovenian, which was extremely uncommon in the mid-19th century. Full of national enthusiasm, she advocated the idea of Slavic identity, and in her brief lifetime produced an extensive body of poetry, literature and music.

With the expansion of the middle class, the 19th century saw the emergence of artists who were rare examples of female intellectual freedom, and initially asserted themselves beyond Slovenia’s borders. Josipina was the first woman to rise to greater intellectual prominence in Slovenia, to be succeeded by Pavlina Pajk, Luiza Pesjak and Marica Bartol Nadlišek.

Josipina was born at Turn Castle into a family of gentry. Her father died when she was eight, and Josipina was educated and instructed in the ways of the world by her mother and a private tutor, Lovro Pintar, a priest and religious writer. Adding to the subjects she studied, Pintar instilled in the young Josipina enthusiasm for Slovenian and a determination to write in the language. Josipina was also educated in Latin, Italian, Greek and some Slavic languages, and tutored in maths, history, and geography. She also took religious instruction and became an accomplished piano player under Alojz Globočnik.

At first, her work was coolly received. In a letter to Lovro Toman, the historian and writer Janez Trdina thus expressed his criticism, “A woman’s place is in the kitchen, barefoot and pregnant – and not holding a pen! This is not her vocation!” He subsequently acknowledged that Turnograjska’s works merited recognition and preservation for future generations.

In a brief creative life that spanned only a few years, Josipina first wrote a large number of short instructive stories with a moral message, Popotnik, Svoboda, Domoljubje, Povračilo (Traveller, Freedom, Patriotism, Restitution), and later on addressed more complex subjects, including historical tales, stories dealing with political events and the significance of the Slavic identity, including Vojvoda Ferdinand Brannšveigovski in francoski v vojski vjeti vojaki, Katarina, ruska carica, Poljski rodoljub, Svoboda (Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick and French Soldiers Prisoners of War; Catherine II, Empress of Russia; Polish Patriot; Freedom). One of her most notable works is Nedolžnost in sila – povest o Veroniki Deseniški (Innocence and Force – a Tale about Veronika of Desenice). Josipina’s literary female protagonists possess supernatural powers, often embody heroic virtues and are also known to resort to weapons.

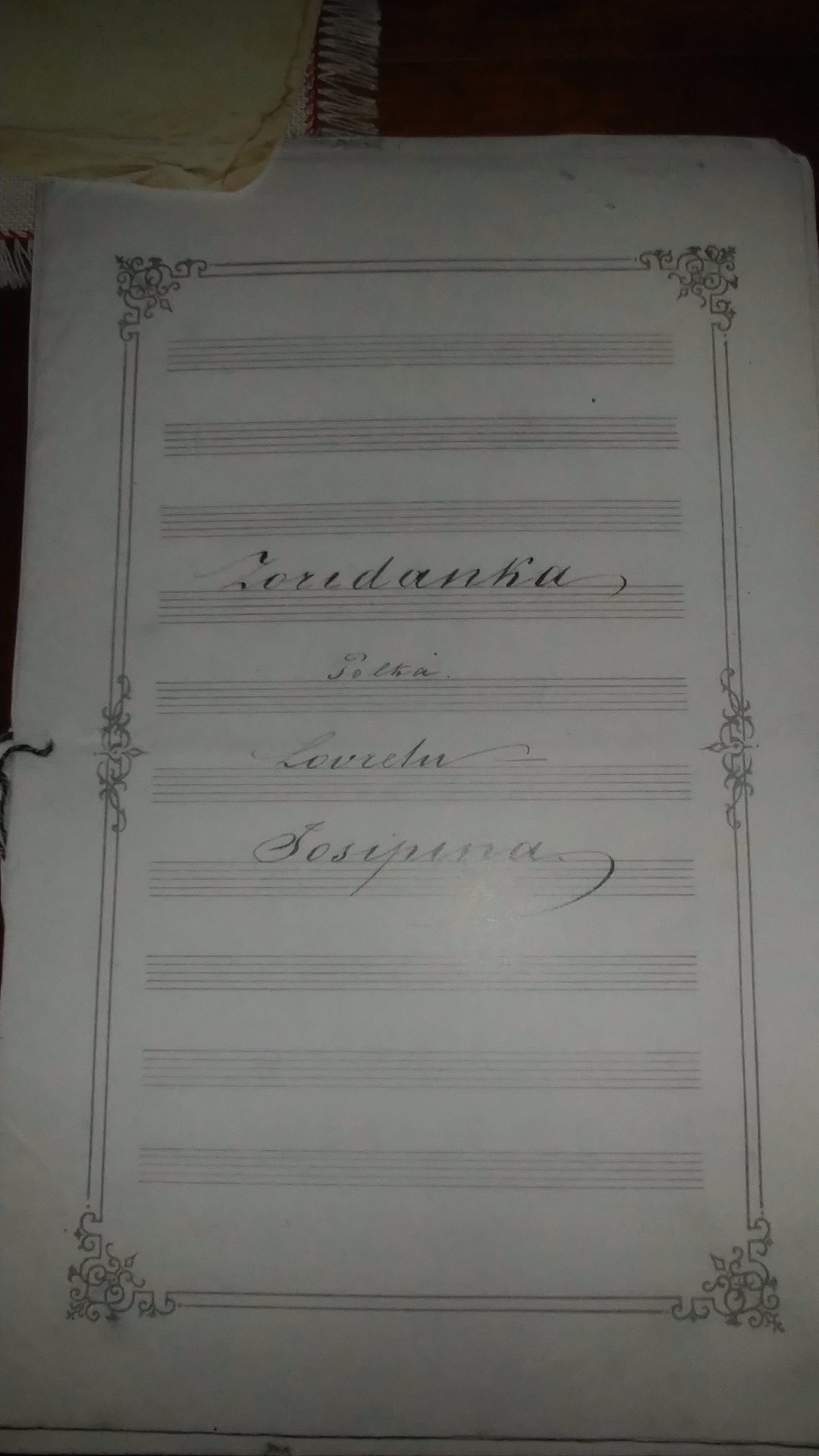

Although few of her compositions have survived, Josipina is considered to be the first Slovenian female composer. She began composing at the age of 17. Her first composition, one of the few manuscripts to survive, is a setting of a poem by Lovro Toman, Tri rožice (Three Flowers). Her compositions exhibit the artistry of a well-versed musician and pianist, and a sensitive composer of melodies based on Slovenian lyrics. The musical texture of her work is built on the classicistic structure. Josipina’s musical setting of her husband’s text, Občutki (Feelings), was performed in 1851 in Graz at béseda, a cultural event organised by Slovenian university students in which music played a patriotic and nationalistic role. In 1864, the composition was selected for inclusion in the music magazine Gerlica (Dove) by its editor, Jurij Flajšman. Turnograjska’s other compositions that are known to have been performed at that time are Napitnica (A Toast), and piano pieces Rodoljubice, Spominčice, Milotinke (Patriotic Songs, Forget-me-nots, Tender Songs) and Zoranka (Aubade), a polka.

Josipina also tried her hand at composing a singspiel, based on the poem The Baptism on the Savica by France Prešeren, which recounts the story of Črtomir and Bogomila. She was doubtlessly drawn to the poem’s theme that at the time promoted the Slavic identity, which served her aim to foreground the nascent sense of national belonging. The work is unfinished.

In 1853, Josipina married and went to live with her husband to Graz, where she died only a year later after a combination of complications at childbirth and measles, aged barely 20. She is buried in Graz at the St Leonhard-Friedhof Cemetery.

Maia Juvanc