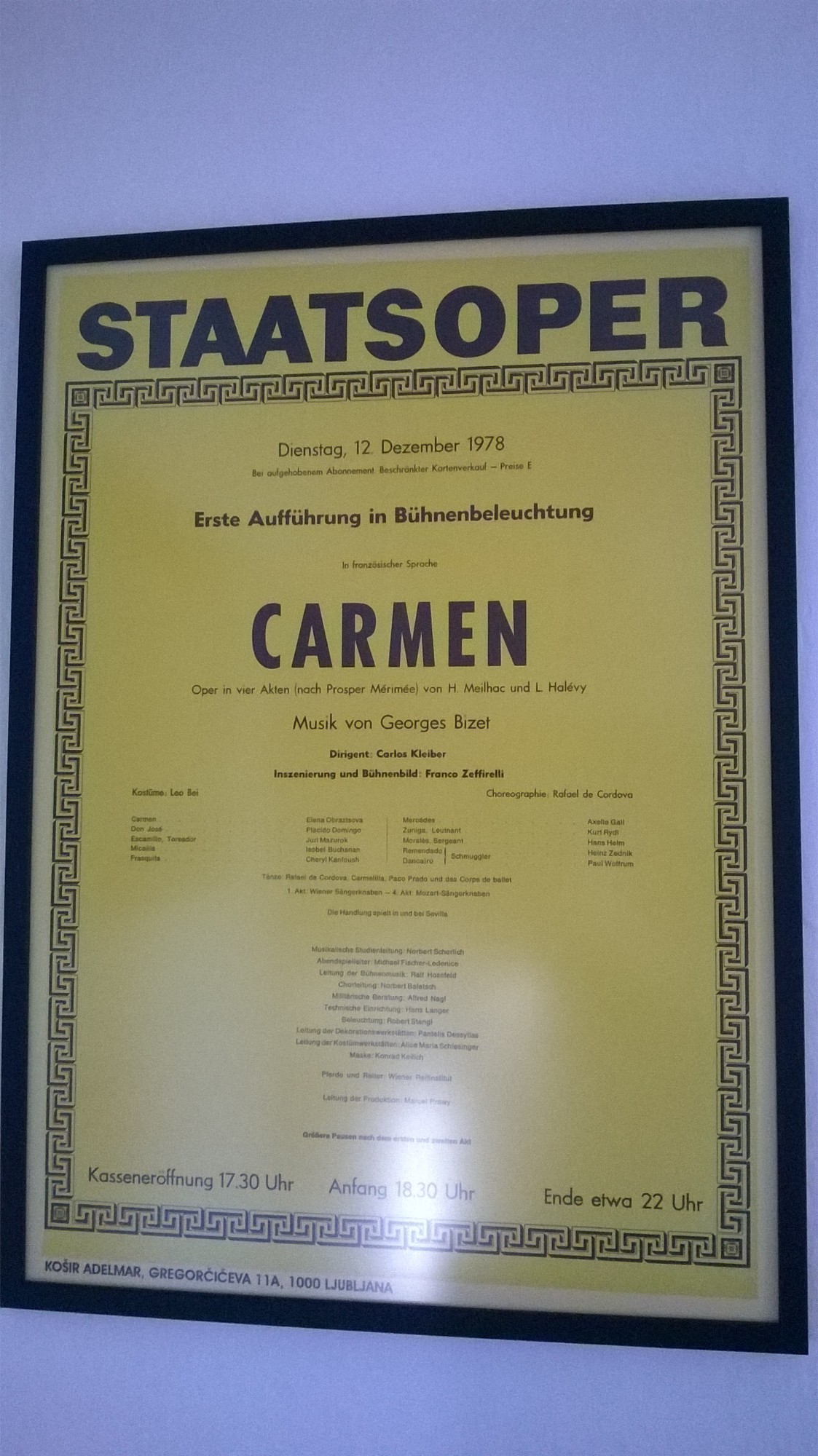

The village of Konjšica is the final resting place of illustrious conductor Carlos Kleiber, who withdrew from the hectic pace of professional life to live in pristine nature in the environs of Litija. Offering a glimpse into Kleiber’s private life and musical career, a memorial room was opened to the public in Konjšica, reflecting in its plain furnishing his modest personality, but offering a highly resonant insight. Appealing to classical music lovers, the exhibition includes a display of Kleiber’s private pictures and provides an overview of his concert appearances in international venues. Also on show are reviews of his performances.

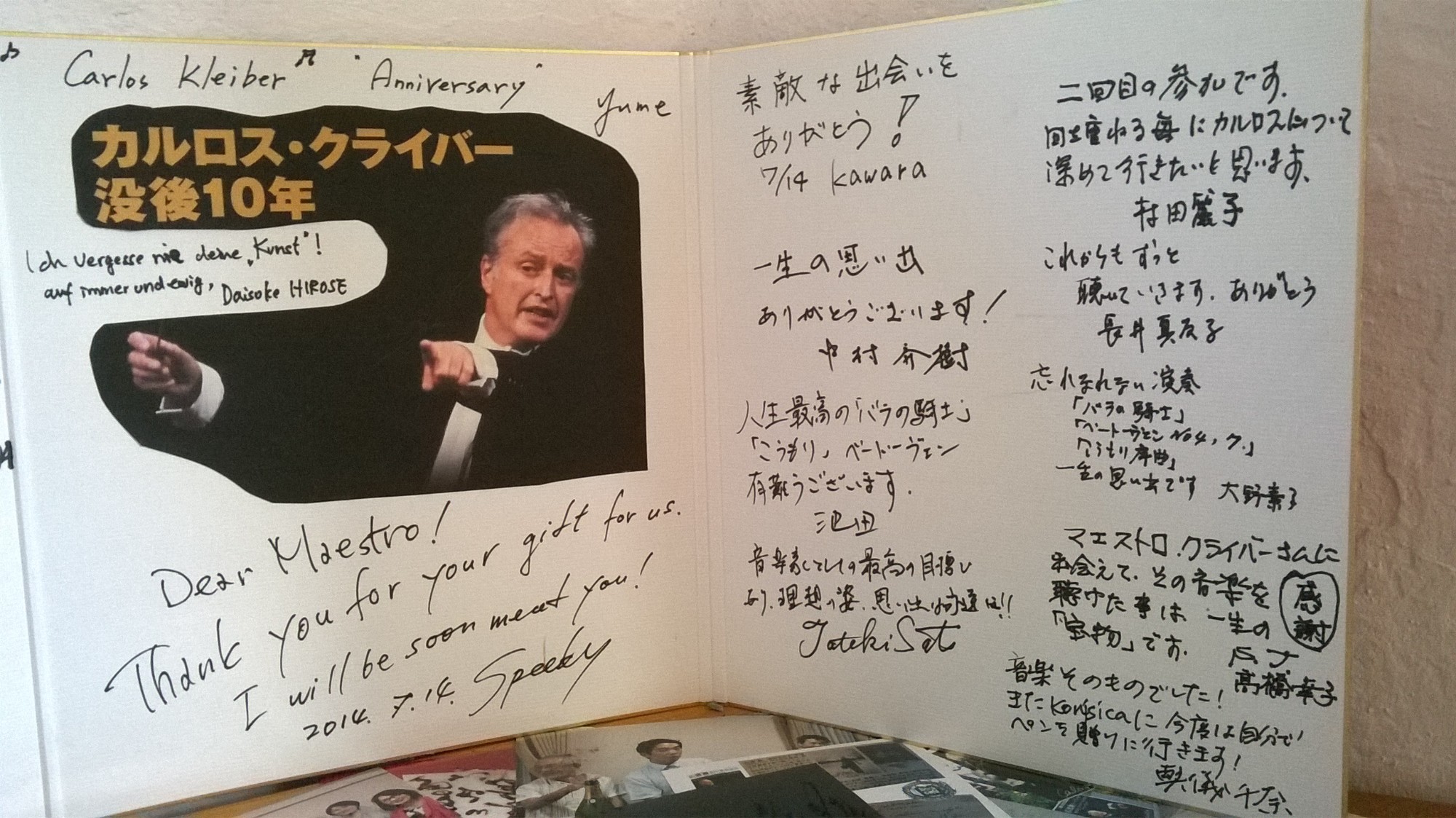

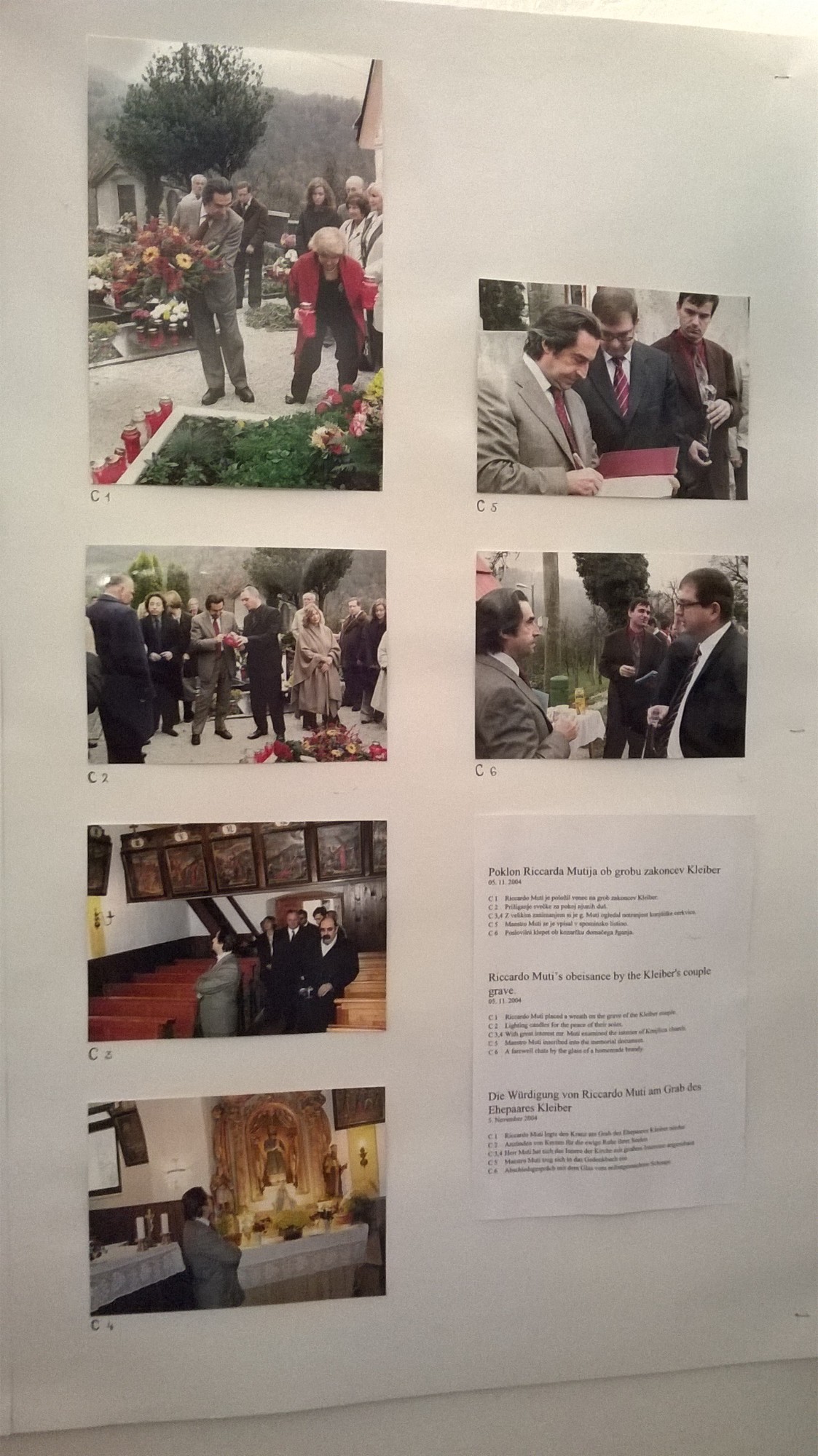

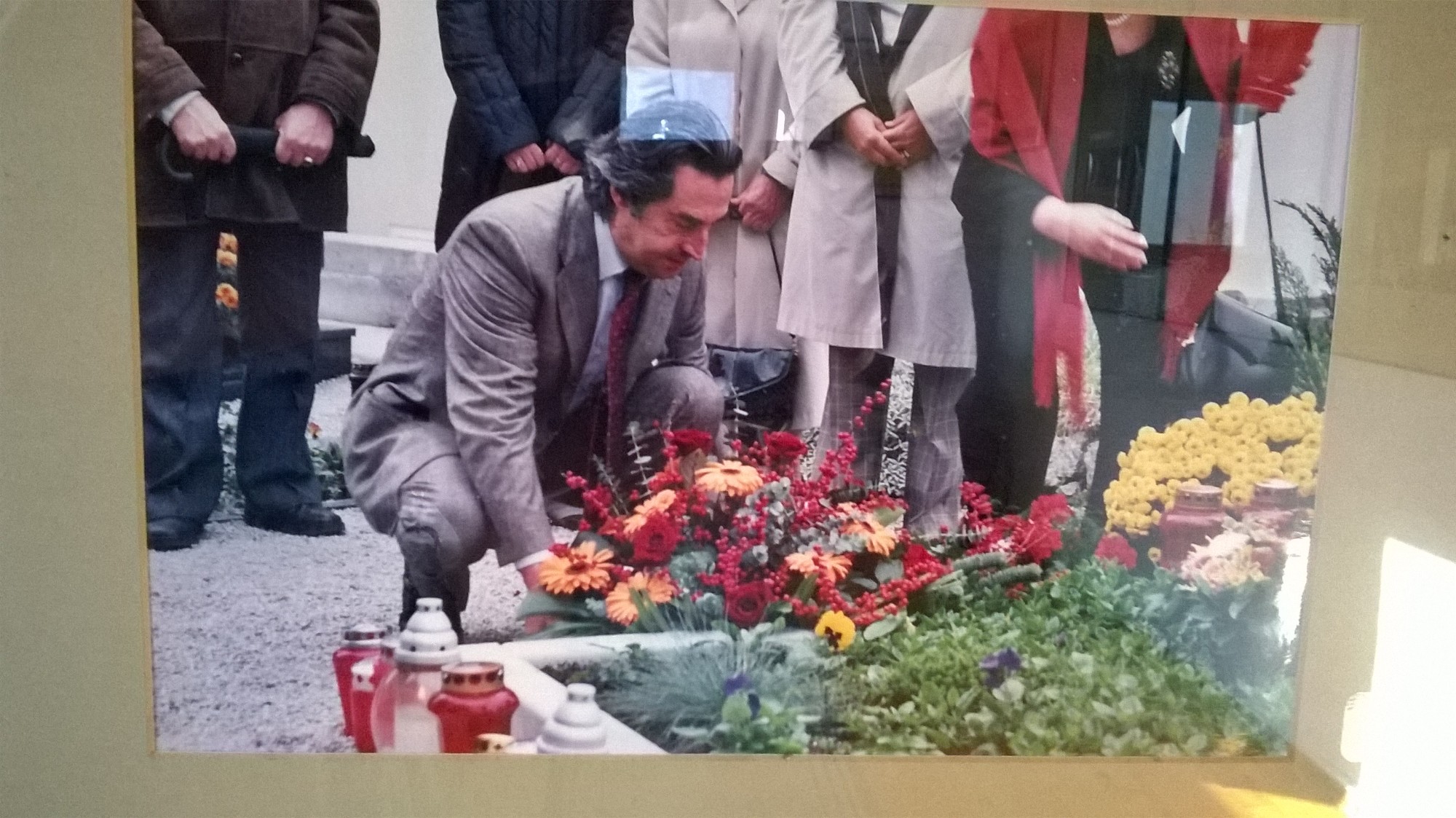

The joint grave of Carlos Kleiber (1930–2004) and his wife, Stanislava Brezovar (1937–2003), is located close to the entrance to the house. According to accounts of the villagers, this pre-eminent twentieth-century composer made a home for himself in the secluded village with his spouse, a ballerina. Broken in spirit after his wife’s death, he passed away seven months later. He could have opted for a glorious grave in Vienna, Berlin or Buenos Aires, but he chose his wife’s native town as his burial place. The people of Konjšica learnt the truth about the couple’s artistic greatness only after their death, when, in late July 2004, a grand memorial ceremony took place in the village, attended by representatives of Slovenia in Austria. The grave has been visited by distinguished musicians, including Riccardo Muti and Valery Gergiev, and occasionally groups of admirers from Japan.

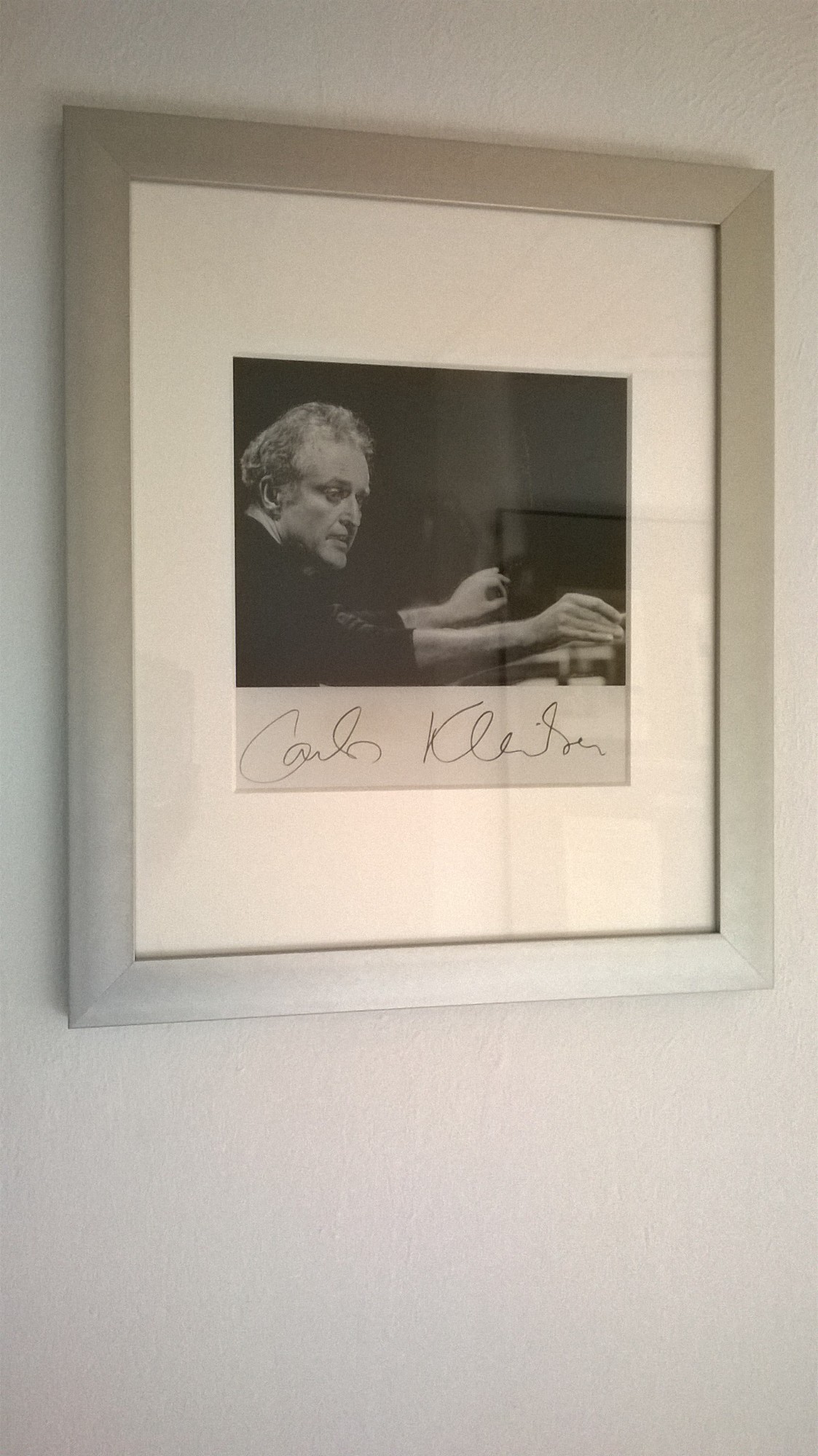

Carlos Kleiber

Carlos Kleiber (1930–2004), widely regarded as being among the greatest and most sought-after conductors of the 20th century, greatly valued his privacy. Distrustful of the attentions of the public, he satisfied his need for seclusion and a quiet domestic life in Slovenia. The people of Slovenia were quick to adopt him as one of their own.

Kleiber was born in Germany, to a renowned conductor Erich Kleiber and his American spouse. Finding the Nazi ideology that was gaining ground in Germany unacceptable, the family migrated to Argentina. At first displaying no tendency to follow in his father’s footsteps, the young Kleiber studied chemistry in Zürich. Also, his father dissuaded him from pursuing a music career. Nevertheless, Carlos’s love of music prevailed. Young Carlos soon showed his innate musical talent, which he began to realise almost secretly as a conductor under an assumed name, Karl Keller.

He achieved distinction under his real name by conducting in theatres and opera houses of German-speaking countries. The critics praised his inventive technique and recognised in his style of conducting a unique combination of unerring accuracy and high-spirited, expressive vitality of dance. Kleiber had a great flair for the inner dynamic and psychology of an orchestra, as well as an instinctive grasp of a composer’s musical line. He soon received an invitation from the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and worked with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Opera House in London and La Scala in Milan.

Kleiber’s distinctive personal characteristic was an unswerving loyalty and complete commitment to his artistic vision, which allowed for no career motivation. Although offered substantial fees, Kleiber invariably worked without a signed contract, so as to freely break off his engagement whenever he grew dissatisfied with problematic orchestra members or came to disagree with the policies of an institution. He acquired a reputation as a mysterious and reclusive artist without managers, one unapproachable even to admirers. Highly appreciated for his work, Kleiber was offered numerous engagements, to work either with soloists or large orchestras, but limited his appearances to a select number of occasions. After Karajan’s retirement from the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, he even declined the opportunity to succeed the illustrious maestro as musical director. He did most of his work with the Bavarian State Opera.

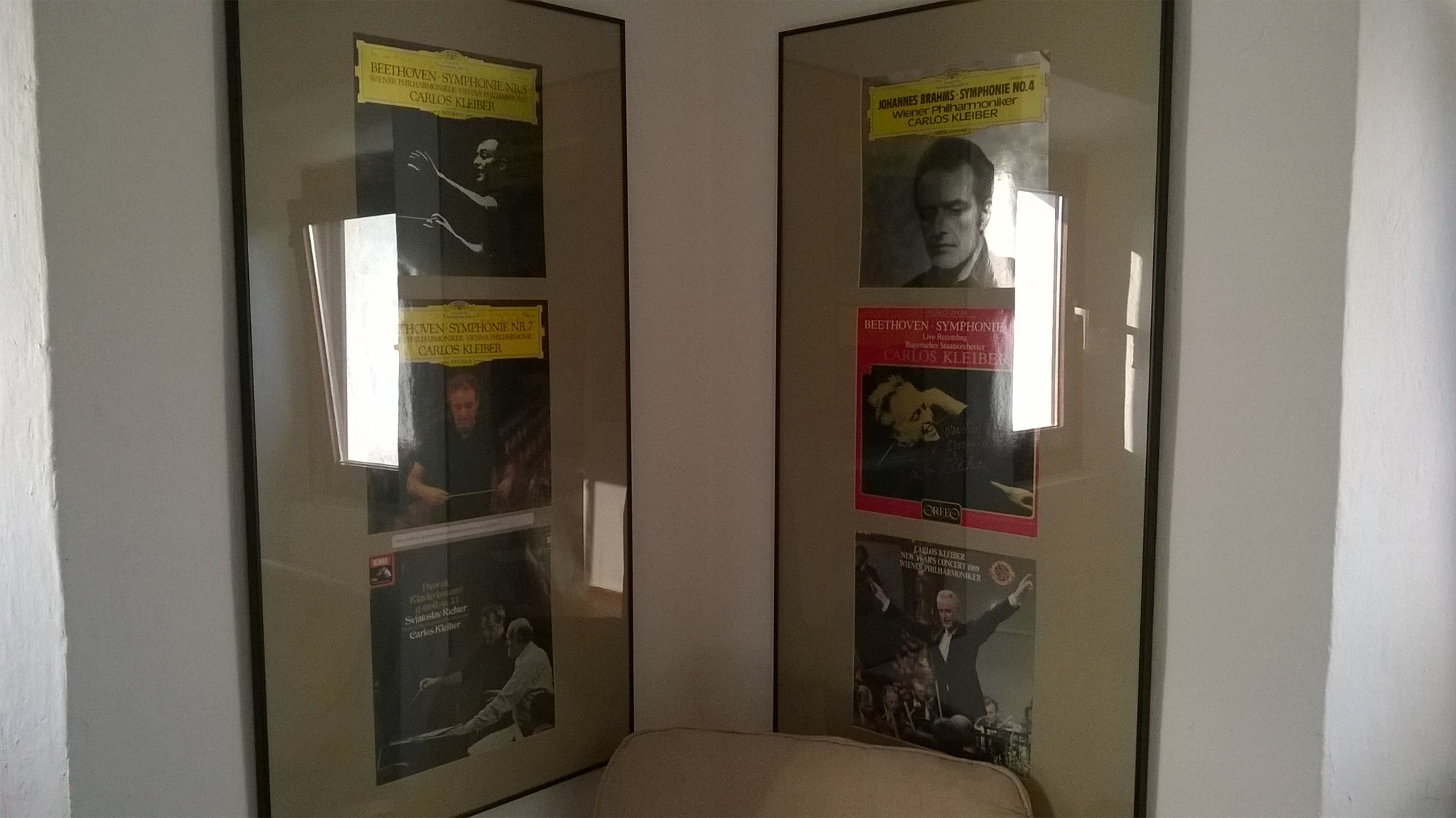

His recording sessions were infamously perfectionist. He would authorise the release of only a handful of his music recordings, which accounts for the paucity of his recording legacy compared to other prominent twentieth-century conductors. Kleiber’s discography is supplemented by live recordings that reveal his charismatic personality and a baton technique that articulated his demands with an almost balletic grace, which lends further insight into Kleiber’s unparalleled interpretative fluency. His most notable recordings include Beethoven’s symphonies with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (Deutsche Grammophon DVD) and the Vienna Philharmonic, Weber’s Der Freischütz with the Staatskapelle Dresden and a New Year’s Day concert with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1989. His finest studio achievement was Beethoven’s Fifth and Seventh Symphonies, a CD that belongs in the pantheon of great recordings.

Kleiber’s appearances with the Slovenian Philharmonic Orchestra and the RTV Symphony Orchestra were exceptional events, although these performances did not lead to a more lasting collaboration. It is interesting to note that, in 1997, Kleiber conducted the Slovenian Philharmonic Orchestra in a performance of Brahms’ Symphony No. 4, Op. 98, whose live recording has been posted on YouTube by an admirer.

A recluse by nature, Kleiber and his wife, Slovenian ballerina Stanislava Brezovar, withdrew from public life to live in seclusion in Konjšica in the vicinity of Zagorje ob Savi, where they bought a holiday home. Although he gave only one interview in his life, and little was known about his private life, his attachment to Slovenia was common knowledge. The Kleibers never spoke of his artistic career, and the local people were unaware of their neighbour’s illustrious past. It was only after seeing Kleiber’s image on an album cover in a record shop that they realised, to their astonishment, that this was after all their modest fellow townsman. Quite unpretentious, Kleiber spoke fluent Slovenian, and liked to stroll in the woods clad in baggy pullovers and threadbare sweatpants.

After his wife’s death in December 2002, Kleiber succumbed to depression. Seven months later, in Konjšica, Kleiber was making arrangements for his wife’s tombstone, which he personally selected and had manufactured. The day after the tombstone was erected, Kleiber was found dead in their cottage. In keeping with his wishes, Kleiber was buried next to his wife in the local graveyard. A special type of rose, grown in Vienna especially in honour of the maestro and named the Kleiber Rose after him, has rambled profusely over the grave.

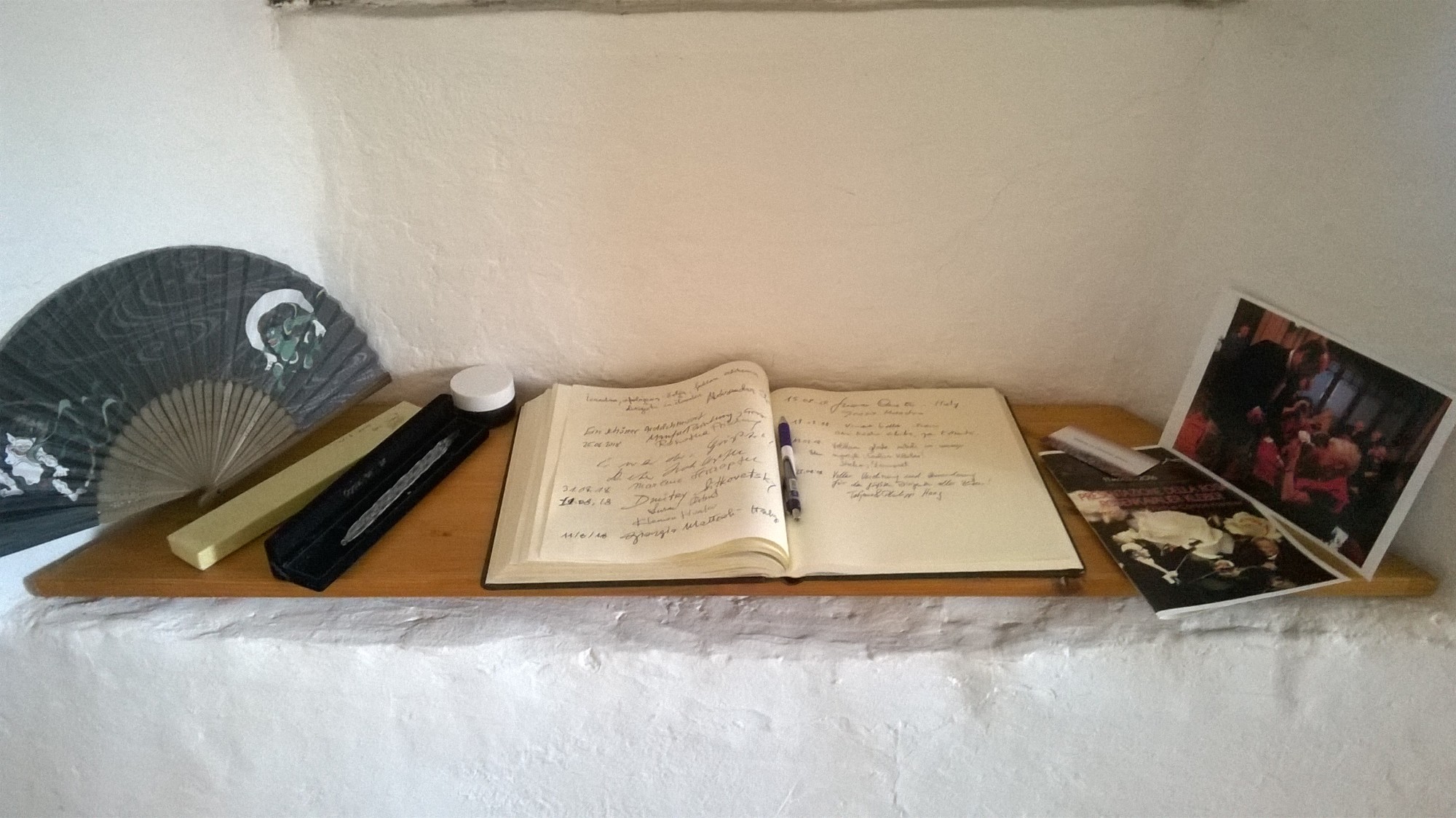

His grave is a pilgrimage site visited by music lovers from all over the world. In 2010, acclaimed conductor Riccardo Muti paid tribute to Kleiber by giving a concert in Ljubljana. A modestly furnished memorial room has been opened to the public in Kleibers’ holiday home, which reflects his unassuming character and brings to mind the fact that one of the greatest, globally acknowledged conductors chose Slovenia for his last home.

Maia Juvanc