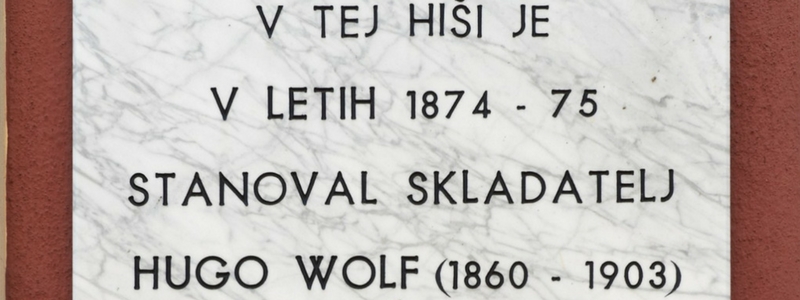

In 1995, on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the University of Maribor, a commemorative plaque to Hugo Wolf was attached to the façade of the building at 5 Mladinska Street. The composer lived in this house from 1874 to 1875. The plaque bears an engraved inscription:

COMPOSER

HUGO WOLF (1860–1903)

LIVED IN THIS HOUSE

BETWEEN 1874–75

ON THE 20TH ANNIVERSARY OF

THE UNIVERSITY OF MARIBOR

16 OCTOBER 1995

Hugo Wolf

Hugo Wolf (1860–1903) was born in Slovenj Gradec. With his prolific and prodigious output of late-romantic lieder, Wolf continued the legacies of Schubert and Schumann and emerged as one of Vienna’s internationally most prominent composers and an idiosyncratic fin-de-siècle figure.

In the 18th century, when still bearing the Slovenian version of their name, Vouk, the Wolf family moved from Šentjur near Celje to Slovenj Gradec. Inheriting the family trade of furriery and tannery, Hugo’s father Philipp, also a keen musician, zealously strove to nurture the musical talent of his son, who in his hometown was soon recognised as a child prodigy with a great flair for music. It was already as an infant that Wolf demonstrated his exceptional musicality and perfect pitch in playing piano and violin. To broaden his artistic horizons, young Hugo moved to Austria, and spent most of his short and tragic life there. Studying at the Vienna Conservatory for a brief spell, Wolf was able to embark on his composing career early on through the support of patrons, and went on to win musical glory as a master of lied.

The bulk of Wolf’s output is embedded in the idiom of romantic lied. In time, Wolf enhanced this expressive musical language by expanding his tonal space and integrating Wagnerian influences. Along with these more progressive elements, his lieder retain the defining characteristics of the tradition inherited from Schubert and Schumann. In his compositional choices, with his subtle feel for poetry, Wolf tailored music to text to provide a profoundly expressive rendering of a song. His composing techniques were remarkable for their harmonic configurations, melodic fabric, vocal declamation, piano texture and the relationship between the vocal line and the piano accompaniment. Searching for an art that was “written in blood”, he immersed himself fully in poetry to re-imagine it through musical means – with overpowering music composed for epicureans, not devotees, as Wolf once claimed himself.

Richard Wagner was Wolf’s greatest musical idol; he inspired in him the desire to compose grander, larger works. Modelling his views on Wagner’s example, Wolf formulated a rather radical (for that time) music aesthetic, while professing a strong aversion to Brahms’ conservative work.

Wolf would suffer from depression and abrupt mood swings throughout his life, and was therefore completely devastated by Wagner’s death in 1883. Wolf’s song, Zur Ruh, zur Ruh, composed soon after Wagner’s distressing death, is considered to be one of his finest early compositions. It is speculated that the piece was written in an elegiac style as an expression of valediction and respect for his idol. Feeling the loss of Wagner’s guidance, Wolf was repeatedly overcome by a sense of despair in the ensuing years. However, his compositions soon captured the attention of Franz Liszt, who suggested – similarly to Wolf’s other mentors – he turn his hand to larger musical forms. Acting on his advice, Wolf composed a symphonic poem, Penthesilea.

Wolf was an outspoken and trenchant critic. Known as ‘Wild Wolf’ for the intensity and articulateness of his convictions, his acerbity made him many enemies.

Abandoning his activities as a critic in 1887, Wolf embarked on a prolific composing period during which he completed Italijanska serenada (Italian Serenade) for string quartet, which is regarded as one of the high points of his mature instrumental compositional style. The years 1888 and 1889 were highly productive for Wolf: escaping to the pastoral idyll of the holiday cottages of his friends, he applied himself to the main genre of romanticism, lied, scoring countless art songs based on poems by Eduard Friedrich Mörike and Joseph von Eichendorff, a monumental Goethejev cikel (51 Goethe-Lieder) and Španska zbirka (Spanish Songbook). Through these compositions, the world outside Vienna now came to recognise Wolf as well; his works were praised in reviews, including in the Münchener Allgemeine Zeitung, a German newspaper with a wide circulation.

In 1891, Wolf’s mental and physical health deteriorated again. Exhaustion, combined with the effects of syphilis and his depressive temperament, forced him to stop composing for the next several years. Continuing concerts of his works in Austria and Germany spread his growing fame, making even Brahms and the critics who had previously reviled Wolf acknowledge his compositional mastery.

This success did not appease his preoccupation with a larger form, the desire to write an opera. The resulting Der Corregidor is a darkly humorous opera about a love triangle, a topic that Wolf could identify with, as the work mirrored his own romantic triad with the wife of a friend.

After 1897, Wolf’s mental health again took a downturn. Slipping into syphilitic debilitation, Wolf was unable to complete his opera Manuel Venegas. After mid-1899, he could create no musical work at all. Following a failed attempt to drown himself, Wolf was placed in a Vienna asylum.

Hugo Wolf is buried in Zentralfriedhof, the central cemetery in Vienna, where majestic tombstones adorn the graves of many other composers, his contemporaries.

Maia Juvanc