Vegova Street originates from the 19th century, when the ditch alongside Ljubljana’s eastern mediaeval town wall was filled in, and was designed by Slovenian architect Jože Plečnik in keeping with his plan for the urban development of Ljubljana. Plečnik devised the Alley as an important cultural axis lined with major national institutions, including the University of Ljubljana, the former Realka (TN: ‘non-classical’ school focused on living languages and natural sciences), the Glasbena matica Musical Society, the Music School and the National and University Library. Its layout follows the architect’s concept of a monumental municipal artery running from Trnovo Church, along Emonska Street to French Revolution Square, and from there leading down Vegova Street to Congress Square, across Zvezda Park and ending in South Square, which, however, was never completed. Plečnik first began the urban planning of the entire street area in 1932.

This year was of great historical importance for the Glasbena matica Music Society, marking the 60th anniversary of the Society and its publishing house and label, the 50th anniversary of the Music School and the 40th anniversary of its Choir. To commemorate these jubilees, the Matica Society opened a concert hall on its premises, dedicating it to Matej Hubad. The façade of the Matica Society’s building was renovated following Plečnik’s design, as was the park in front of it. A balcony supported by four columns was added and, on the initiative of politician Ivan Hribar, funds were allocated towards the realisation of the Avenue of Slovenian Composers. Whilst a committee for the monument dedicated to Davorin Jenko was initially set up, the desire to honour the memory of Jenko provided the impulse to erect further memorials to composers, as well as the principal of the Glasbena matica Music School.

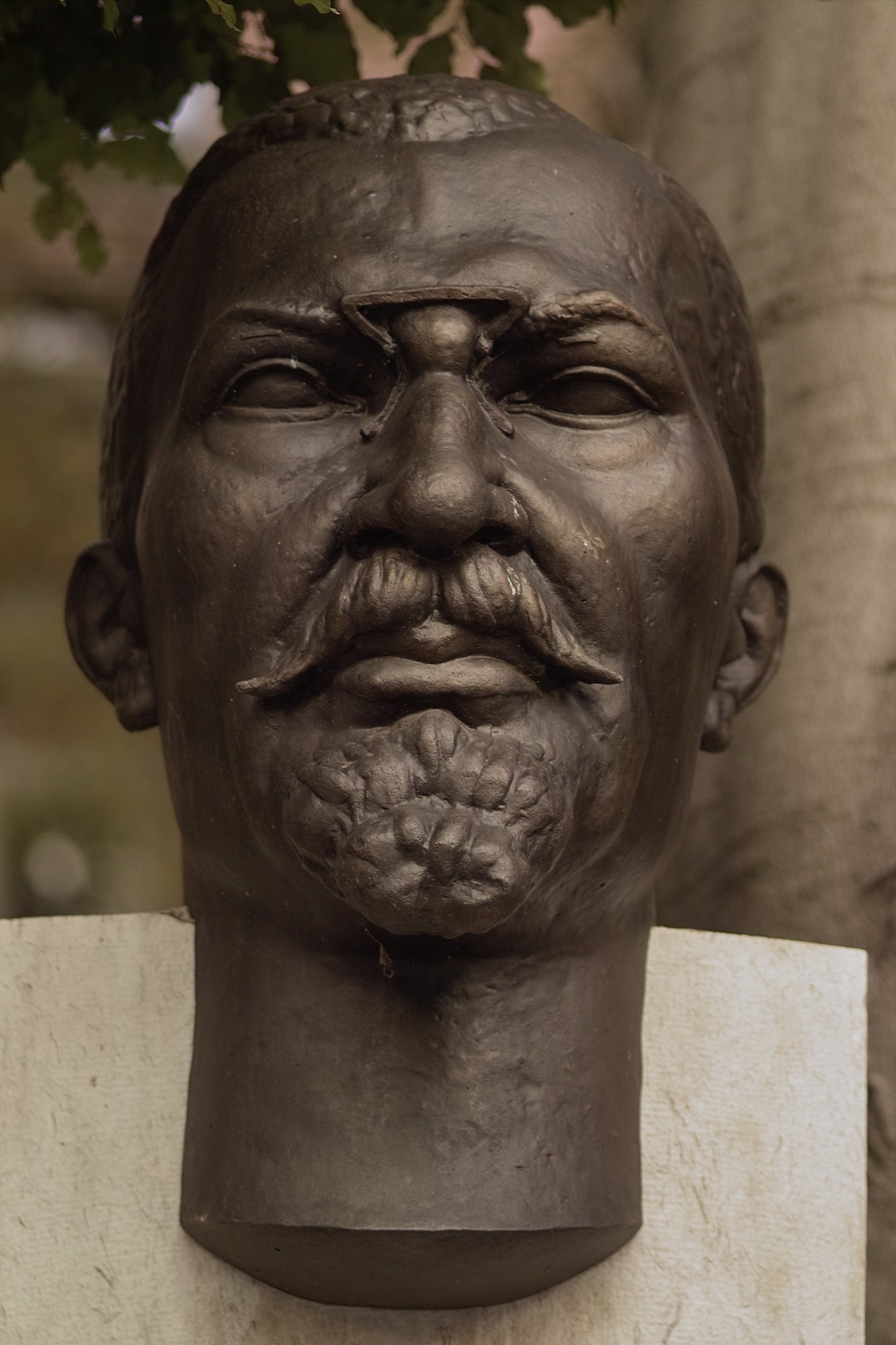

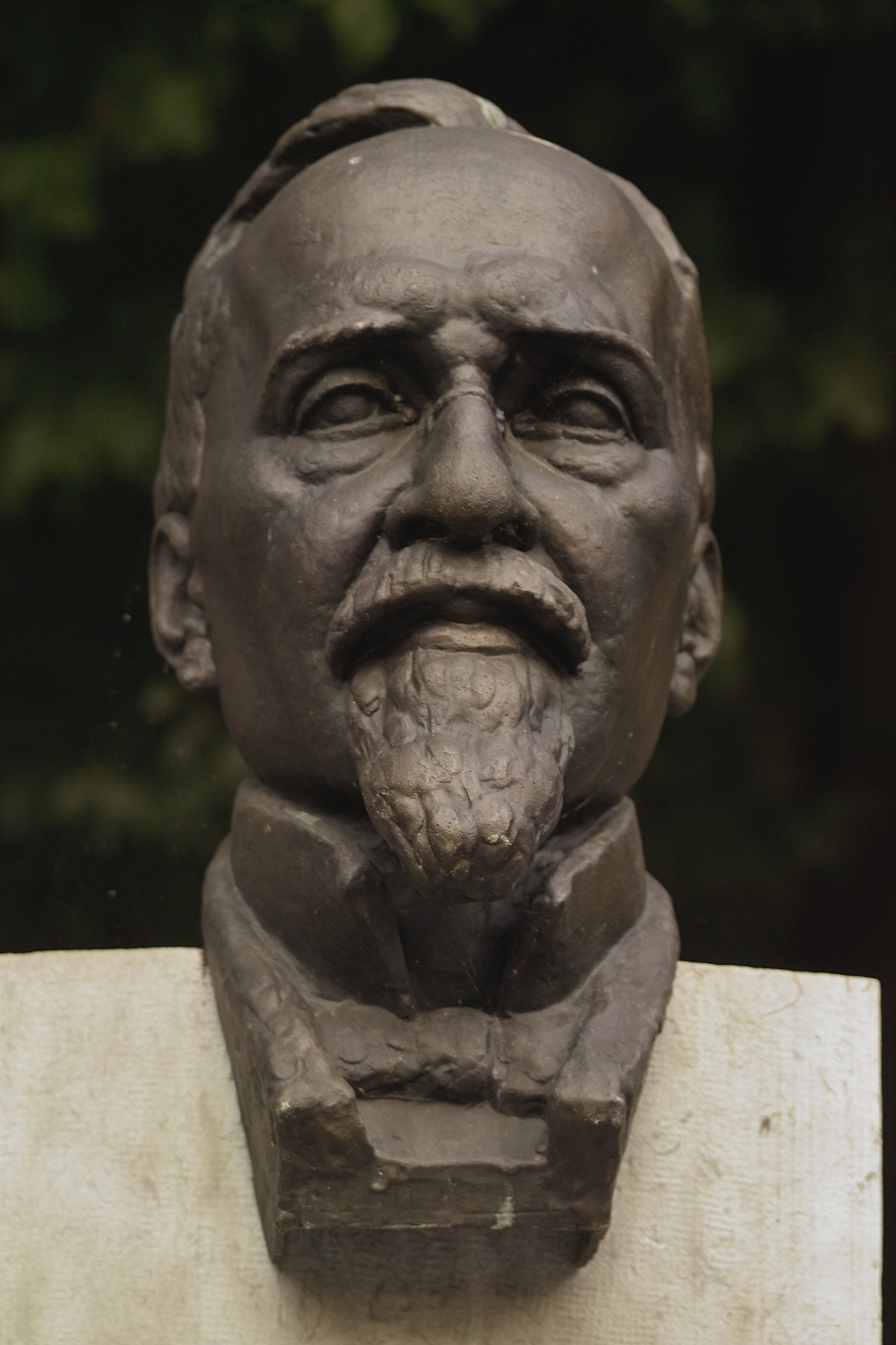

The Alley and its eight monuments were formally inaugurated on 16 May (1932) as part of the concluding event of the First Slovenian Music Festival. Besides the monuments to the principal of the Matica Conservatory of Music, Matej Hubad, and to the first principal of the Matica Music School, Fran Gerbič, the memorials unveiled during the inauguration ceremony were dedicated to Benjamin Ipavec, Vatroslav Lisinski, Jacobus Handl Gallus, Davorin Jenko, Stevan Mokranjac and Hugolin Sattner, all made by sculptor Lojze Dolinar. Subsequently, in 1937, on the centennial of the birth of Anton Foerster, a statue of this composer and educator was added, and a year later, posthumously, a monument to composer Emil Adamič.

Maia Juvanc & Tanja Benedik

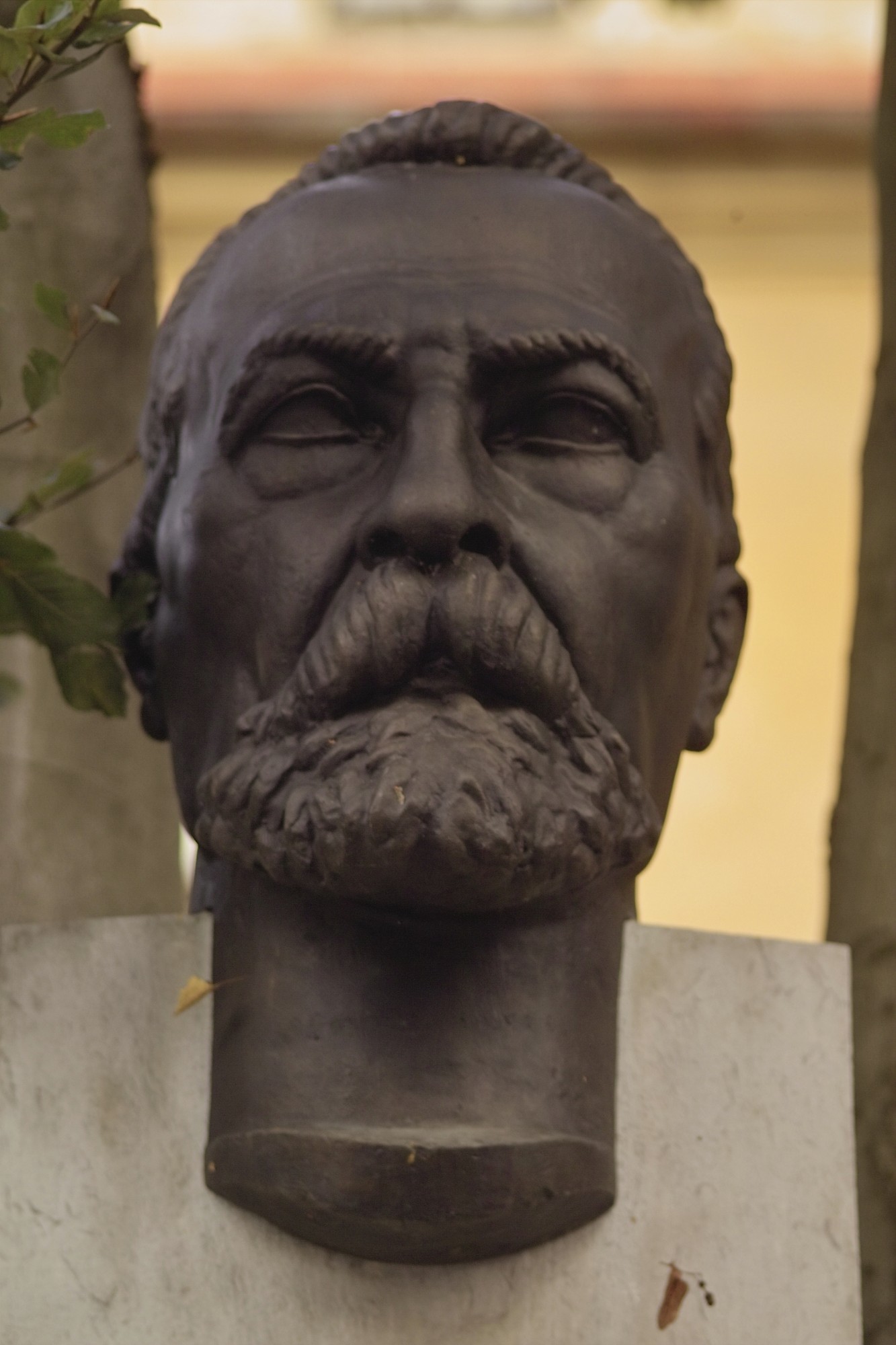

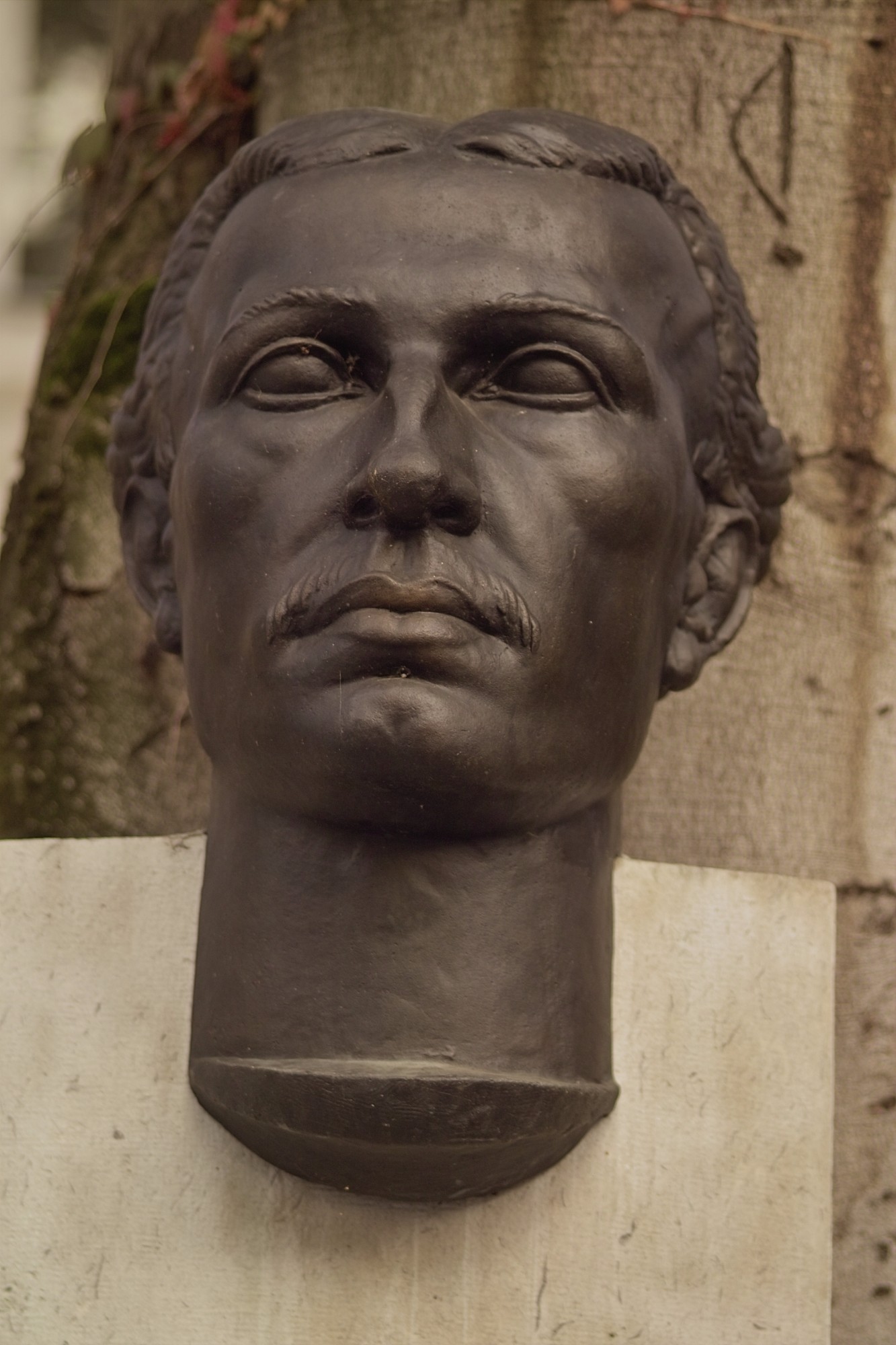

Vatroslav Lisinski

The eminent Croatian composer Vatroslav Lisinski (1819–1854) left his mark in Slovenia as an iconic figure of Croatian national music and an adherent of the Illyrian movement. He wrote the first opera in Croatian, Ljubav i zloba (Love and Malice), and Porin, an opera held to be his finest work.

Lisinski, whose father was a Slovenian from Novo mesto, was born in Zagreb. He devoted most of his life to composing influential works in his hometown, employing the early Romantic idiom and laying the stylistic foundations for Croatian art music. He received further musical training in Prague under the composer Karl František Pitsch and opera composer Jan Bedřich Kittl. Lisinski scored lieder, choral music and piano pieces in addition to operas.

Maia Juvanc

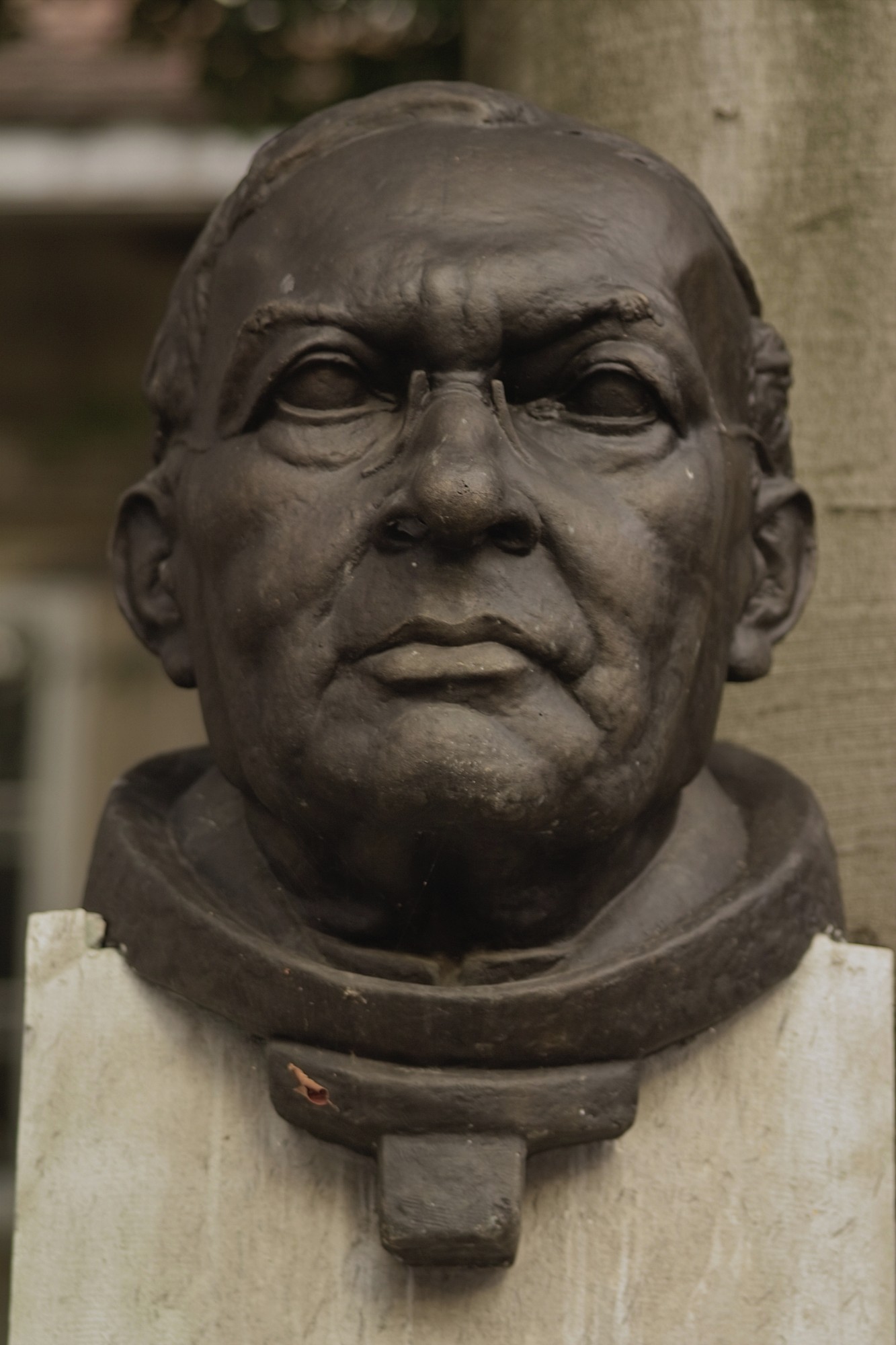

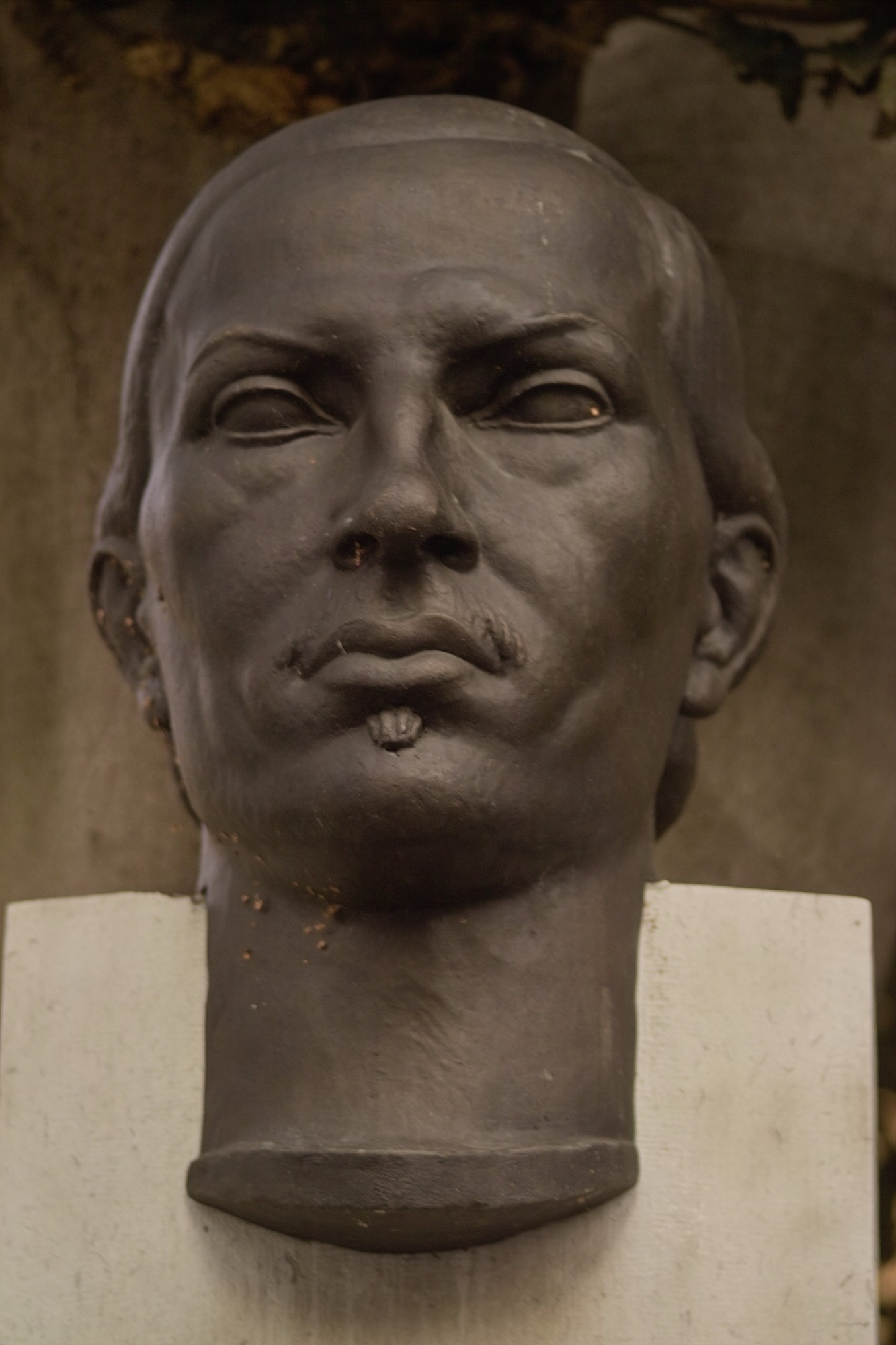

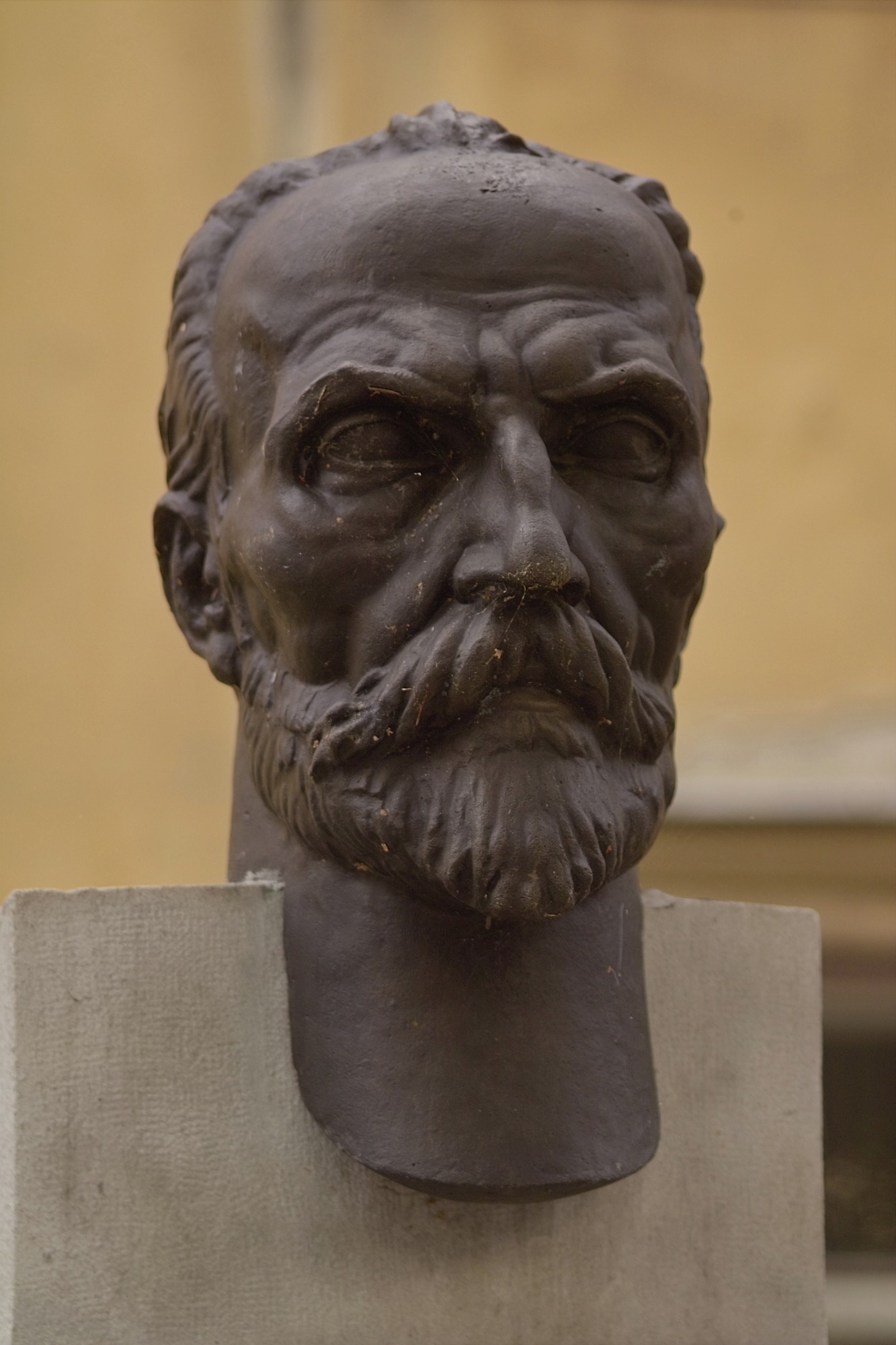

Stevan Mokranjac

With his extensive oeuvre, the Yugoslav romantic composer and choirmaster Stevan Mokranjac (1856–1914) marked both the Serbian and Slovenian musical landscapes.

His stimulating domestic environment, a family of enthusiastic singers, inspired the young Stevan’s interest in music. He was especially drawn to the Serbian Orthodox Church chants. Early in his composing career, Mokranjac transcribed liturgical choral works and re-imagined them in his singular vision by removing the microtonal elements and ornamentation and reharmonising them. His remodelling of Orthodox Church choral music, investing it with a characteristic sound that distinguishes it from other Eastern Orthodox liturgical chants, was favourably received and widely adopted. He also composed several pieces of religious music in a dense polyphonic style similar to that of the Renaissance composer Palestrina.

He took up academic studies first in Belgrade and then in Munich with Josef Rheinberger, where he learned more about the music of Richard Wagner. It is presumed that Mokranjac was the first Yugoslav musician to visit Bayreuth, where he supposedly attended a production of Parsifal some months before Wagner’s death. He pursued further studies in Rome under Alessandro Parisotti and in Leipzig under Salomon Jadassohn and Carl Reinecke. In terms of style, he adhered closely to romanticism, but placed greater emphasis on reinventing and incorporating folk elements, which is a characteristic feature of his work. In this respect, Mokranjac succeeded Kornelije Stanković, the initiator of Serbian romantic music.

He treated folk melodies as material on which to base his original artistic creations. The widespread popularity of Mokranjac’s output is attributed by some to the finely proportioned measure of sophisticated technical elaboration of his harmonic idiom and the simplicity of folk motifs. Some regard Mokranjac’s preference for drawing themes from folk tradition as a gradual detachment from romantic ideas and the beginnings of folk realism, or naturalism; furthermore, his works are considered to be the principal model for the introduction of early modernism into Serbian music.

Folk elements are prominent in the choral suites Venčki (Rukoveti or Garlands), which musicologists consider to be the cornerstone of the Serbian art music canon. Venčki comprise several series of Serbian folk songs (deriving from Macedonia, Kosovo, Montenegro and Bosnia), which the composer stylised and stylistically adjusted to make into a coherent whole, and adapted for unaccompanied singers. His compositions became popular with choirs throughout the former Yugoslavia, after being premiered by the Belgrade Choral Society. He became the conductor of this choir in 1887, a position he held until his death. Societies of this kind were the driving force of cultural life at the turn of the nineteenth century. Mokranjac’s compositions were also included in the repertoire of the Glasbena matica Music Society Ljubljana, the sole publisher of his works in Slovenia. It was due to Matej Hubad’s advocacy that the composer’s music was regularly featured in the Slovenian concert repertoire long after Mokranjac’s death.

Maia Juvanc

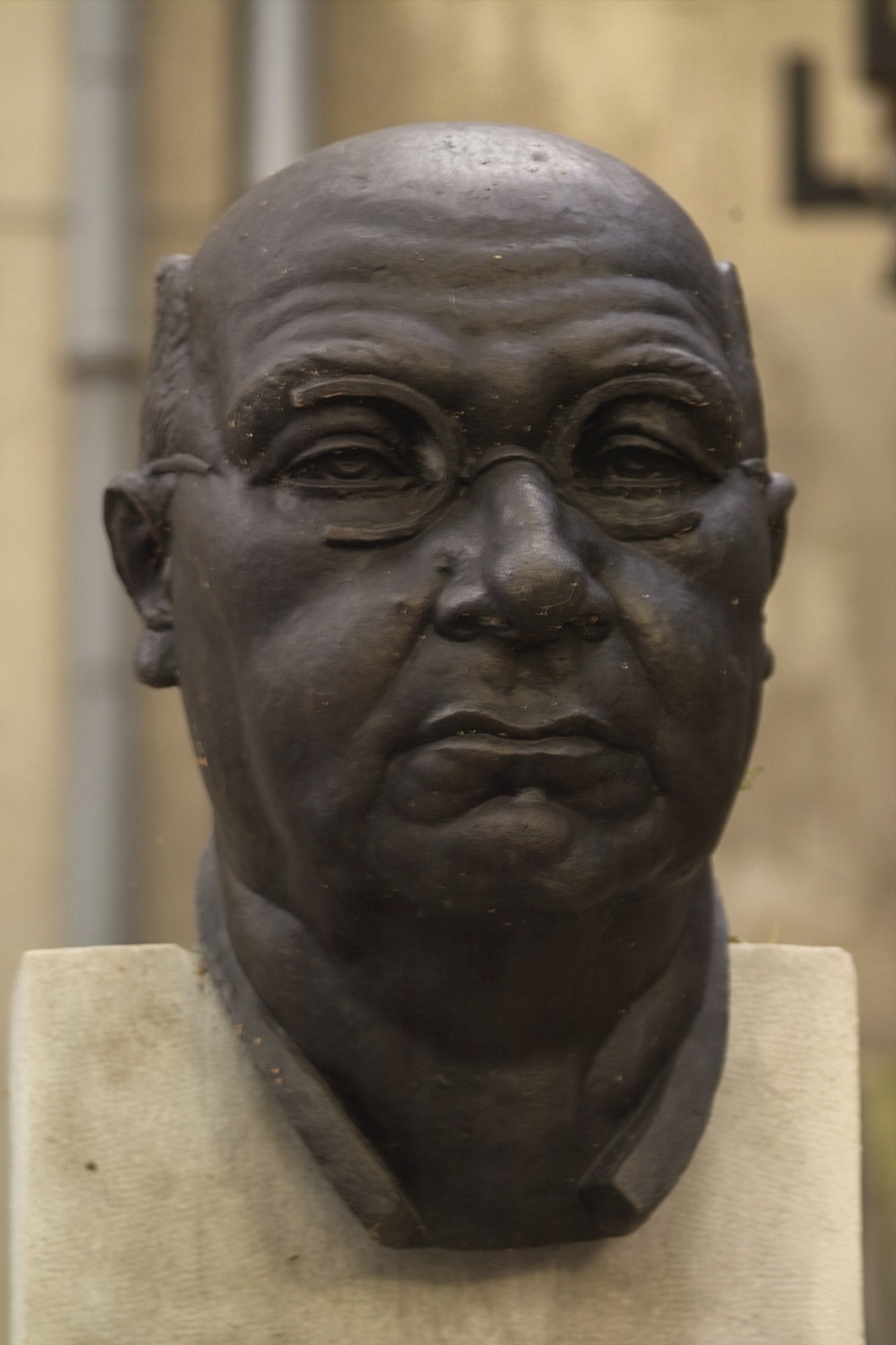

Matej Hubad

You can read the biography HERE.

Fran Gerbič

You can read the biography HERE.

Benjamin Ipavec

You can read the biography HERE.

Jacobus Handl Gallus

You can read the biography HERE.

Davorin Jenko

You can read the biography HERE.

Hugolin Sattner

You can read the biography HERE.

Anton Foerster

You can read the biography HERE.

Emil Adamič

You can read the biography HERE.