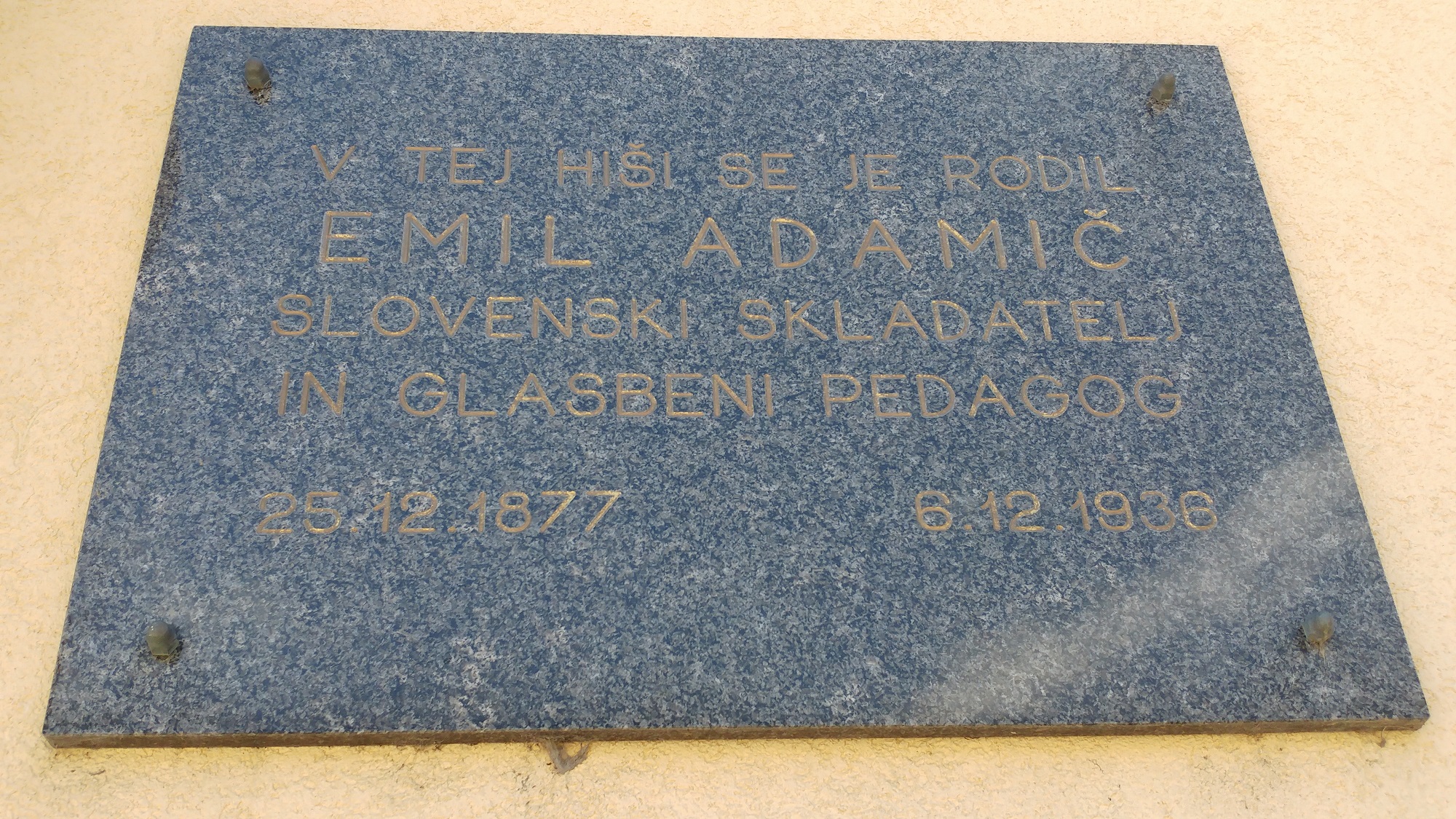

A black marble memorial plaque attached to the birthplace of Emil Adamič was formally unveiled in Dobrova near Ljubljana in 1977.

Emil Adamič

Born on Christmas Day in Dobrova, on the outskirts of Ljubljana, Emil Adamič (1877–1936) asserted himself in the early twentieth century as one of the pre-eminent Slovenian composers of vocal and orchestral music. Unlike his contemporaries, Adamič worked in a wide range of genres; it is not only his prolific choral body of work that is exceptional, but also his chamber and symphonic music and lieder. Displaying similar diversity in terms of style, his musical idiom comprises elements ranging from folk diatonicism and romantic melodiousness to the chromaticism of New Objectivity, as well as elements of impressionism and expressionism, also incorporating sounds produced by factory machinery, a characteristic feature of Russian Futurist music. Adamič also worked as a music critic and publicist and was editor of the Nova muzika magazine.

His first musical education consisted of piano, music theory and harmony lessons that Adamič received from his father and at the School of the Glasbena matica Music Society in Ljubljana, where he studied violin with Edvard Stiaral, and music theory and singing with Fran Gerbič. In early adulthood, he followed the family tradition and enrolled at the Ljubljana Teacher Training College, studying under Anton Foerster. He attended the Music School of the Glasbena matica Music Society Ljubljana, studied harmony with Matej Hubad, and took violin lessons in his final year at the Teacher Training College with the renowned Ljubljana violinist Hans Gerstner.

In autumn 1911, while working in Trieste, Adamič enrolled in the fourth year of composition at the Trieste Conservatory of Music, purportedly leaving the school in June 1912 and completing his education in Ljubljana by passing the state examination in 1922 at the Conservatory of the Glasbena matica Music Society. Adamič studied composition at the Academy of Music in Zagreb, and also took lessons informally, especially with tutor Gregor Gojmir Krek, who instilled in him an interest in contemporary compositional methods that overrode the simple harmonisations of the late nineteenth-century period of the Reading Societies, the intellectual clubs aimed at raising Slovenian national consciousness.

Taking a sabbatical, the composer travelled the length and breadth of Yugoslavia, collecting folk tunes, which came to markedly influence his compositional style. Later on, Adamič passed the state examination for music teachers at the Ljubljana Music Conservatory and began teaching at the State Male Teacher Training College, while also serving as choirmaster of numerous choirs, including Lira Kamnik, Zarja Trieste, Venezia Giulia Teacher Choir, Glasbena matica Music Society Teacher Choir, and as its co-founding member, the Trboveljski slavček Choir. He occasionally also conducted the Orchestra of the Glasbena matica Music Society’s Orchestral Association.

Choral music makes up the bulk of Adamič’s oeuvre; besides lieder, he wrote vocal compositions for various ensembles (four-part, mixed, female and male choirs). It is the melodiousness of folk song that characterises his early choral output, including Zapuščene, Lipa (Abandoned, Lime Tree), and the widely popular Vragova nevesta (The Devil’s Bride) and Smrt carja Samuela (The Death of Tsar Samuel). While his choral composition from 1923, Viola, reflects influences from expanded tonalities, the composer gradually began to embrace the tendencies of New Objectivity, an artistic current that emerged during the 1920s, with the rise of liberal-democratic ideology under the German Weimar Republic.

The characteristic predilection for objective sobriety professed by the New Objectivity movement is inherent in the polyphonic musical texture of Tri duhovne pesmi (Three Spiritual Songs), Trije mešani zbori (Three Mixed Choirs) and the more widely known Šaljivke (Scherzos). In his programmatic choral works – throughout his middle creative phase – Adamič enhanced expressive elements by using secundal and whole-tone chords, vocal shrieks and declamation, which the influential Slovenian composer Lucijan Marija Škerjanc, a devoted upholder of tradition, compared to the choral works of Paul Hindemith and dismissed as pieces on the verge of non-musicality.

Echoes of new twentieth-century European artistic currents can be found also in Adamič’s orchestral works, composed at a time when he was actively involved with the Orchestral Association of the Glasbena matica Music Society Ljubljana. Iz moje mladosti (From My Youth, 1922) is a prominent example of orchestral music, a genre previously neglected in Slovenian musical circles. It features motifs from Slovenian folk songs, while the programme of extra-musical narrative is vividly rendered in the harmonic texture, displaying distinctive diatonic, whole-tone, chromatic and pentatonic methods. Over this period, Adamič composed another original and visually suggestive programmatic suite, Ljubljanski akvareli (Ljubljana Watercolours, 1925), whose diverse modulations and broad range of musical forms express the contrasting moods in various familiar parts of the city.

Adamič most fully adopted avant-garde tendencies in his final piece, a ground-breaking work in terms of composition, Tri skladbe za godalni orkester (Three Pieces for String Orchestra, 1936), where he discarded programmatic titles and utilised extreme means of expression, ranging from whispering to clangourous sounds in the manner of Russian Futurists (Alexander Mosolov) to realistically imitate factory machinery.

For his innovative compositional idiom, Emil Adamič, alongside Slavko Osterc, is seen in the history of Slovenian music as a forerunner of contemporary artistic currents and departures from late Romanticism, an aesthetic that became firmly established in Slovenia, resting on the ideology of social realism, and which continued into the second half of the twentieth century.

Maia Juvanc